Writing as Discovery

On knowing when and what to write ...

“The secret of seeing is, then, the pearl of great price.” –Annie Dillard

I recently heard that when asked about writing the Lord of the Rings stories, J. R. R. Tolkien responded that he “discovered” the stories. He received them with a knowing that he needed to bring them to life.

I’ve seen this a lot with writers who tell me that the idea just came to them, and they felt compelled to write. What moves us from the direction of discovery to bringing a story to life?

I think it has to do with the virtue of noticing.

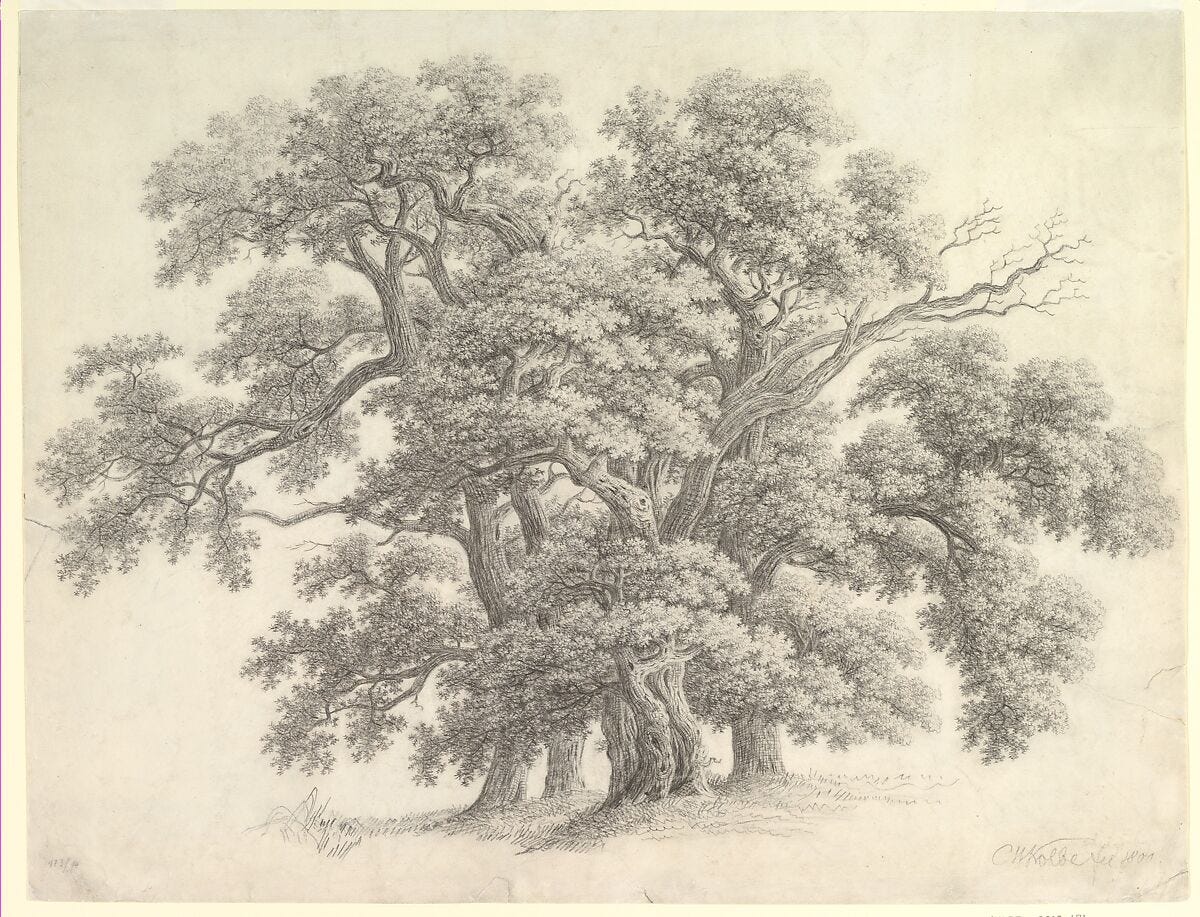

On a fall walk with my daughter, we passed by our neighborhood’s morning bus stop. The students waiting for their bus were all hunched over their phones. While standing together, they appeared alone. No one noticed the sunlight slanting through the orange leaves of the maple tree or the sound of squirrels scurrying up the towering oaks. Their phones seemed to betray their distance from reality—and one another. My daughter interrupted my own gaze when she pointed to an unbroken acorn to take home—a rare find on a road covered in crushed acorns. My daughter’s focus on this one small object helped me understand the fragility of our attention. Her noticing jolted me out of my own hardened gaze.

As a writer, I think about what I see a lot. I fear a loss of seeing well because what we perceive is tied to our humanity. Novelist and philosopher Iris Murdoch goes so far as to say that “as moral agents we have to try to see justly.” Throughout my day, I see many of the same things—nothing particularly interesting, or so it seems. For Murdoch, seeing isn’t a passive act, but rather it takes a discerning mind and moral effort on our part. What does it take to steward that kind of attention and fine-tune our seeing?

The Writing Life

The writing life is not only an act of resistance to the demands on our attention, but it is also an act of faith—of seeing the beauty, truth, and goodness as evidenced through the world we experience. It’s a life of looking, waiting, silence, and seeking. Writers are tasked to express what they’ve seen and to recognize the extraordinary in the mundane. It’s a practice that preserves our ability to think and observe. When we stop observing, we incline ourselves toward passive absorption of information. As Flannery O’Connor reminds us in Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, “Your beliefs will be the light by which you see, but they will not be what you see and they will not be a substitute for seeing.”

I’ve found that when I began a writing life, I had to notice the world more. When my writing became too abstract, I had to search for imagery and sensory details to bring the ideas back down to earth. I had to get back into reality when my head was clouded with vague and abstract ideas. Whenever I stopped writing, I also stopped noticing. Writing demands keen observations of the world around us. It keeps our gaze centered on the concrete and the real. In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard writes, “Seeing is of course very much a matter of verbalization. Unless I call my attention to what passes before my eyes, I simply won’t see it. It is, as Ruskin says, ‘not merely unnoticed, but in the full, clear sense of the word, unseen.’ … I have to say the words, describe what I’m seeing.”

Writing to Remember

When we returned home from our walk, my daughter put her acorn in her nature box. In each compartment of the box, she places her acorns, leaves, rocks, or other findings. This curated box of treasures signifies her memories of finding a piece of sea glass or a whole acorn. Rainer Maria Rilke said, “Perhaps creating something is nothing but an act of profound remembrance.” When we write, we do something similar. We labor through finding the words to express what we think and what we see. We also unearth the memories deep inside us that might help us connect the dots.

Writing keeps us close to the earth, so we never miss a treasure to keep.

What I’ve been up to

My poem “Earthworms” was published in the Winter Collection in Ekstasis, a journal from Christianity Today.

What I’ve been reading

I love that poetry was something that drew them in relationship. I think their relationship itself was a kind of poem, with two layers of meaning—the literal and the metaphorical. Relationships with this hidden, metaphorical meaning invited me to keep reading their story as something more than a tale of romance.

Thank you for reading A Holy Wonder — your support allows me to keep doing this work.

If you enjoy A Holy Wonder, invite your friends to subscribe and read with us. If you refer friends, you will receive some awesome benefits!

How to participate

1. Share A Holy Wonder. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

2. Earn benefits. When more friends use your referral link to subscribe, you’ll receive special benefits.

Get a PDF guide on “Cultivating the Creative Life One Habit at a Time” for 5 referrals

Get a FREE copy of my book Behold: A Reflection Journal Where Wonder, Creation, and Stewardship Meet for 10 referrals

Get editorial feedback on any essay (up to 1,000 words) for 15 referrals

Thank you for helping get the word out about A Holy Wonder!